Like all good exhibits, What’s Still Here, What Came Before Us started with a conversation over a cup of coffee. Liz Ranney and Nicole Young approached me two years ago to pitch their idea for an art exhibition in Lake Country. We sat outside and sipped coffee as Liz and Nicole shared their ideas, thoughts and vision. They wanted to do something that can make some artists shudder, including myself: Collaborate.

Painting can be an isolated endeavour. Artists spend weeks, months, and years on their self-imposed islands of creativity, narrowly focusing on their own ideas. For some artist, sharing this solitary experience can be intimidating. But Ranney and Young wanted to jump head first into it.

Art, like everything, cannot exist in a vacuum. Paintings do not spring onto canvases fully formed without influences and inspirations. Society, politics, philosophy, culture, and a laundry list of other elements feed into art. Artists take the noise from the world and filter it into something striking, something bold, something that makes us think.

Ranney and Young have made that influence explicit with this exhibit. They used the lyrics from Leila Neverland to inspire their paintings. They plumbed the depths of another medium to create a unique vision for the gallery. Three artists, all with their individual experiences, talents, and perspectives, came together to build a unified series of paintings.

But when you walk into the gallery, do you see that collaboration? When you study the paintings, do you see the work of one artist? Two artists? Three? Maybe more? Is the collaboration clear as day? Do the two painters’ styles stand out? Or is the line separating their techniques completely blurred? Did Ranney, Young, and Neverland successfully merge their styles into one voice? Does such a fusion matter with collaboration? When artists work together, should they maintain their individual voices? Should they completely meld together? Or should it be something in between? I hope these paintings provoke similar questions for you as you absorb the exhibit.

Art history, of course, has many examples of collaborations. Numerous artists have made some their best work when they team-up with like-minded people. Some of the most popular and enduring art pieces have come from collaborations. A quick google search brings up:

Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat

Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray

Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns

Pablo Picasso and Gjon Mili

Luis Bunuel and Salvador Dali

Chuck Close and Philip Glass

Bjork and Matthew Barney

Marina Abramovic and Ulay… to name but a few.

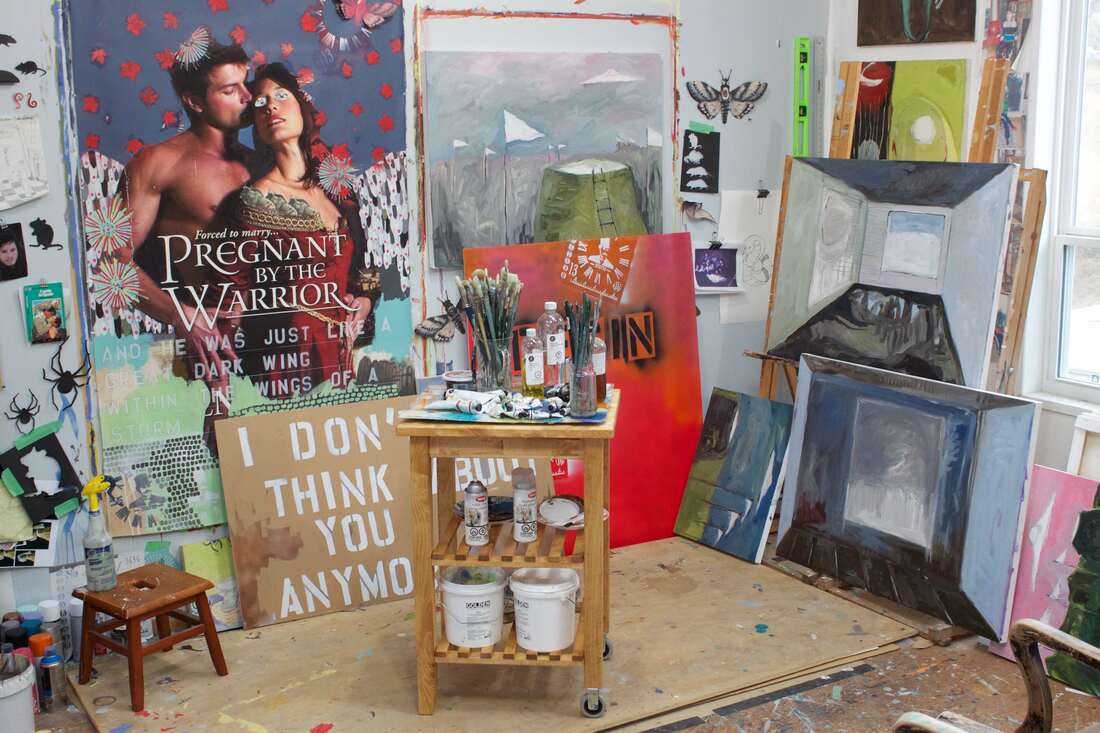

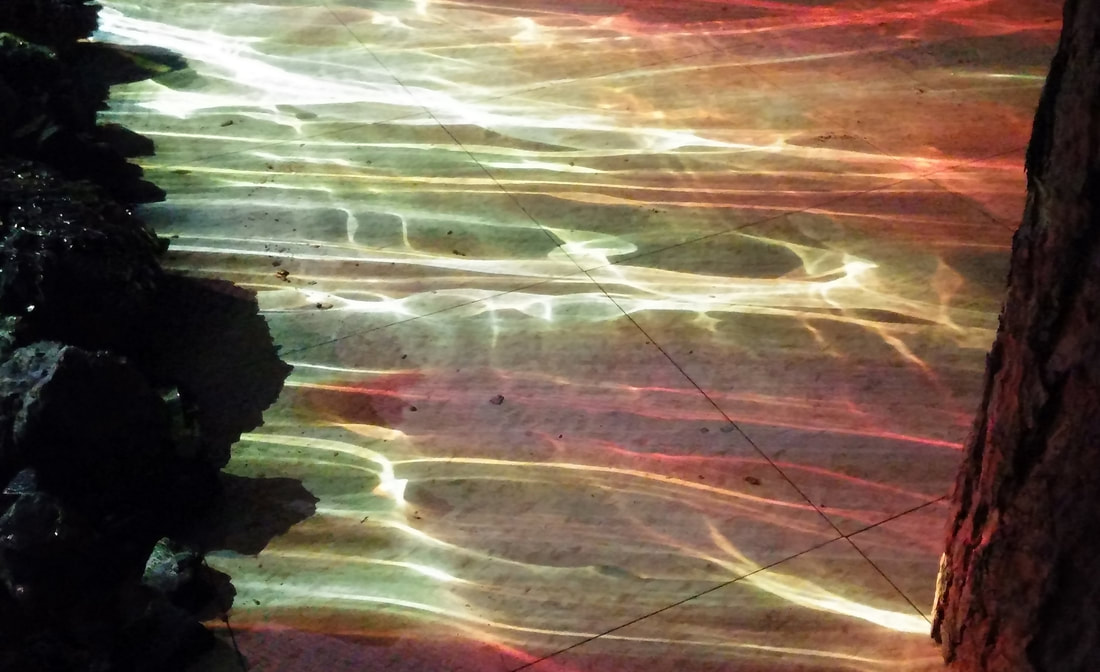

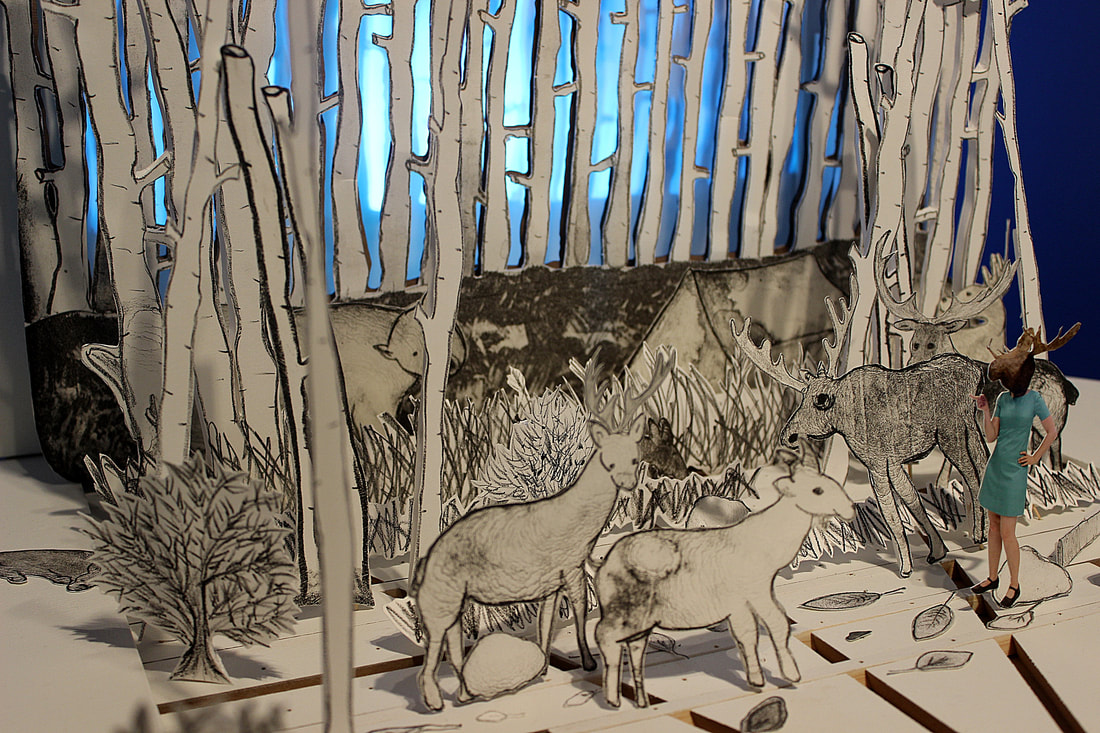

When you enter the gallery you happen upon a series of paintings, a wall ‘collage’ and an installation in the back of the gallery.

Each painting and installation in the gallery is accompanied with a set of notes. A dialogue

between the three artists is recorded…contemplation, reflection, questions, ideas and lists of colours are scribble across sheets of paper.

viridian green + parchment

muted grey + titan buff

phthalo turquoise

yellow oxide

nickel azo gold

quinacridone magenta

carmine

brownish paint water

For example, Leila Neverland’s words, ‘You can hide all you want, but those spirits will haunt ya…you can hide, under those covers, but you’ll never see the stars…you’ll never see the stars and the spirits will haunt ya’ , form the foundation for the painting Under Cover. Ranney and Young take these words and build a composition with paint, fabric, line and texture. By interpreting these lyrics and the back and forth of the canvas between Ranney and Young, a final image comes together.

As a viewer, you’re a collaborator. Gallery exhibitions create a relationship between you and the artist. You bring your own perspective and experience to bear when you study art. You define the meaning of each piece on your own terms. This exhibition is a celebration of how we all work together to discuss, debate, and build something new. In our daily lives, we’re all collaborators.

Even this introduction is a collaboration between writer Sean Mott and curator Wanda Lock.

Sean Mott is a reporter, a writer, and an amateur knitter. He’s written plays, short film scripts, theatre reviews, and novellas. His work has been featured in publications in Nova Scotia, Saskatchewan, and British Columbia. He’s currently based in Lake Country.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed